Heating Repair Guide

Introduction and Outline: Why Heating Repair Matters

When your heat cuts out on a freezing night, minutes feel longer and decisions get rushed. A clear plan turns that stressful moment into a manageable checklist. Heating is among the largest energy uses in homes—often around 40% in cooler regions—so timely repairs protect comfort, prevent damage like frozen pipes, and keep energy bills steady. This guide balances safe do‑it‑yourself checks with the realities of professional service, showing you how to troubleshoot, estimate costs, and maintain your system for reliable, efficient operation.

Before we dive deep, here’s the road map we’ll follow so you can skip straight to what you need:

– Section 1: Why heating repair matters, what this guide covers, and how to use it effectively.

– Section 2: System basics—furnaces, boilers, and heat pumps—plus key parts and common failure points.

– Section 3: A practical, step‑by‑step diagnostic flow for no‑heat, low‑heat, short cycling, odors, or noises.

– Section 4: What you can fix, what to leave to the pros, typical repair costs, and decision rules for repair vs. replacement.

– Section 5: A preventive maintenance calendar and a concise conclusion tailored to homeowners and renters.

Two principles drive everything here. First, safety beats speed: if you smell gas (sulfur or “rotten egg” odor), hear arcing, or suspect carbon monoxide, leave the home and call your utility or emergency services. Second, a systematic approach saves money: many “failures” trace back to airflow, power, or control settings. We’ll use plain language and specific examples—like dirty filters, stuck pressure switches, or condensate drain clogs—so you can recognize patterns and act with confidence. Whether your system is forced air, hydronic, or a heat pump, the methods below help you stabilize the situation, communicate clearly with a technician, and make cost‑smart choices that respect both comfort and budget.

Know Your Heating System: Types, Components, and How They Fail

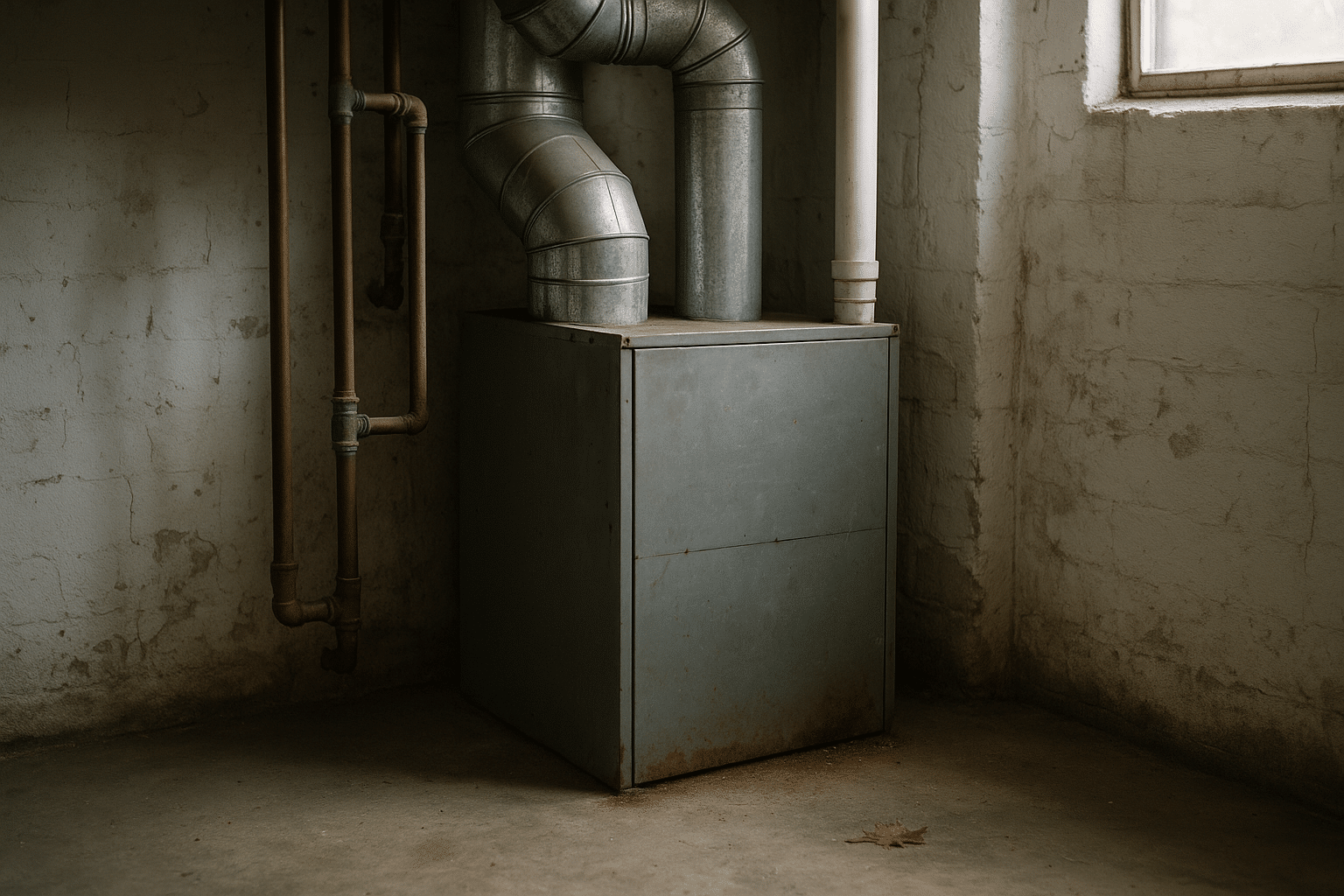

Heating systems fall into three broad families: furnaces (forced air), boilers (hydronic), and heat pumps (air‑source or ductless). Furnaces burn fuel or use electric resistance to heat a heat exchanger, then a blower moves warm air through ducts. Boilers heat water or make steam; circulator pumps and zone valves move warmth to radiators or in‑floor loops. Heat pumps move heat rather than create it, using refrigeration cycles to extract heat outdoors and bring it inside. Each family has distinctive parts and failure modes, so recognizing your setup is step one.

Furnace essentials include a thermostat, control board, safety switches (limit and rollout), an inducer fan to clear exhaust, an ignitor (hot surface or spark), a flame sensor, a blower motor, and an air filter. Typical failure patterns: a cracked or clogged ignitor prevents light‑off; a fouled flame sensor causes the burner to shut down seconds after ignition; a seized or capacitor‑starved blower kills airflow and triggers high‑limit shutdown; a blocked condensate drain on high‑efficiency models interrupts operation. Data point: modern gas furnaces often carry AFUE ratings from ~80% to the mid‑90s; airflow restrictions and mis‑tuned combustion can quietly erode that efficiency, translating to higher bills and uneven comfort.

Boilers rely on the burner/heat exchanger, expansion tank, circulator pump, air eliminator, pressure/temperature relief valve, and sometimes multiple zone valves. Failures show up as no heat to a zone (stuck zone valve), noisy operation (air in lines), or insufficient circulation (worn pump or clogged strainer). Steam systems add traps and vents that must function to keep distribution balanced. A boiler that short cycles or climbs in pressure may need expansion tank service or attention to controls—issues that, left unchecked, can stress the system and shorten lifespan.

Heat pumps have an outdoor unit (fan, coil), indoor coil/air handler, reversing valve, defrost controls, contactor, and capacitors. Common pain points include icing in cold, damp weather when defrost controls lag; a faulty reversing valve that leaves the unit stuck in one mode; or low airflow from a clogged filter or dirty indoor coil. Because refrigerants are tightly regulated, only licensed technicians should open that circuit. Still, many heat pump “no heat” calls trace back to basics you can check safely: thermostat mode, clogged filters, iced‑over outdoor coils, and blocked return grilles. – Knowing the components helps you separate simple fixes from specialized work. – Matching symptoms to parts guides efficient troubleshooting. – Observing the start‑up sequence often reveals the first place things go wrong.

Step‑by‑Step Diagnosis: From No‑Heat to Odd Noises

When the heat fails, start with safety and power, then move inward. Begin by confirming the thermostat is on HEAT with an appropriate setpoint (try 3–5 °F above room temperature). Check the furnace switch (often a wall toggle near the unit), service disconnects, and the breaker. For gas appliances, confirm the gas valve is open; for oil, ensure you have fuel and do not repeatedly reset a tripped burner without investigation. If you suspect carbon monoxide, exit immediately and address safety before any further steps.

With basics covered, follow a simple flow that applies to most systems:

– Airflow: Inspect or replace the filter; a heavily loaded filter can cause short cycling, poor heat, or limit trips. Open supply registers, and clear return grilles.

– Condensate: High‑efficiency furnaces and many air handlers stop if the condensate pan is full or the drain is clogged. Clean the trap and tubing; look for kinks.

– Ignition sequence: Listen for inducer fan startup, ignition click or glow, burner light‑off, then blower. If it lights and dies within seconds, the flame sensor may be dirty; carefully cleaning it with a fine abrasive pad can restore operation. If there is no glow or spark, the ignitor or controls may be at fault.

– Boilers: Feel supply and return pipes for temperature differences, bleed radiators if airbound, verify circulator operation, and check system pressure and the expansion tank.

– Heat pumps: Inspect the outdoor unit for icing; a light jacket of frost is normal, a solid block is not. Ensure the outdoor fan spins freely and that debris isn’t blocking airflow.

Strange sounds point in useful directions. A screech often suggests a failing blower or inducer motor bearing; a buzz can indicate a weak capacitor or chattering relay; thuds may come from duct expansion and contraction, especially after filter changes that alter static pressure. Odors help too: dusty smells at first start are common as burners and elements burn off residue; sharp electrical smells or persistent smoke are stop‑now warnings. – Document what you observe: sequence of events, sounds, and any error blink codes. – Make one change at a time to avoid masking the real fault. – If a breaker trips repeatedly, or you see scorch marks, do not re‑energize until inspected. A clear log of symptoms saves diagnostic time, reduces uncertainty, and can lower your bill when a technician arrives.

Repairs, Costs, and When to Call a Technician

Some fixes are safe and straightforward; others are specialized for good reason. Suitable homeowner tasks typically include filter replacement, thermostat battery swaps, cleaning a flame sensor, vacuuming a condensate trap, clearing debris from outdoor coils, and bleeding radiators on hydronic systems. These jobs improve reliability and can reveal hidden issues. On the other hand, fuel leaks, combustion adjustments, high‑voltage wiring, gas valve replacement, heat exchanger diagnosis, and any refrigerant work belong to licensed professionals.

Cost expectations help you decide quickly. While prices vary by region and access, you can use these typical installed ranges to plan:

– Service call/diagnostic: roughly $75–$150.

– Tune‑up/inspection: commonly $100–$200, often credited toward repairs.

– Capacitor: about $100–$200.

– Ignitor or flame sensor: roughly $100–$300.

– Thermocouple (standing pilot systems): about $80–$150.

– Pressure switch: roughly $150–$350.

– Blower motor: commonly $400–$800, more for variable‑speed models.

– Inducer motor: about $500–$900.

– Circulator pump (boiler): roughly $300–$800.

– Zone valve (boiler): about $200–$400.

– Heat exchanger replacement can be a major expense ($1,500+), and full system replacement commonly runs into the several‑thousand‑dollar range depending on capacity and efficiency.

Use simple decision rules to protect your budget:

– If repair costs exceed ~30–40% of a unit’s replacement price and the equipment is near the end of its typical lifespan (furnace/boiler ~15–20 years, heat pump ~10–15 years), evaluate replacement.

– If you face repeated failures from the same component, discuss root causes (e.g., high static pressure, poor combustion air, or voltage issues).

– If your AFUE or heat pump efficiency is far below current norms, factor energy savings and comfort gains into the long‑term math.

Selecting a technician is about risk management: verify licensing and insurance, ask how they handle after‑hours calls, and request a written scope with parts, labor, and warranty terms. Look for clear explanations and options rather than pressure. A reputable pro will invite questions, show replaced parts on request, and explain how to prevent repeat failures. That partnership—your observations plus their expertise—delivers reliable heat without unpleasant surprises.

Preventive Maintenance Calendar and Final Takeaways

Prevention turns urgent nights into routine checklists. In late summer or early fall, schedule a heating tune‑up that includes combustion checks (for furnaces/boilers), safety control testing, blower and inducer inspection, condensate system cleaning, and verification of temperature rise within specifications. Replace or wash air filters and clear space around the equipment to ensure ventilation. For hydronic systems, confirm system pressure, bleed radiators, and test circulator and zone valve function. For heat pumps, rinse outdoor coils with gentle water flow, straighten bent fins carefully, and verify defrost operation.

Carry habits through the season:

– Inspect filters monthly and change as needed; many homes benefit from 60–90 day intervals, but pets, renovation dust, and high occupancy can shorten that.

– Keep supply registers and returns unobstructed.

– Watch for icing on heat pump outdoor units after storms; gently clear snow and leaves.

– Listen for new noises at start‑up; subtle changes often precede failures.

– Test carbon monoxide alarms monthly and replace batteries on a schedule.

Off‑season, give the system a post‑mortem. If comfort was uneven, consider duct sealing or balancing; leaky ducts can waste significant heat and drive up runtime. Add weatherstripping to exterior doors, seal obvious air leaks around penetrations, and evaluate attic insulation levels; tightening the envelope can reduce heating load substantially. Smart thermostat features—carefully set—can trim fuel use by reducing temperature during sleep and away periods, especially in homes with predictable schedules.

Conclusion for homeowners and renters: Reliable heat is the result of consistent attention, not luck. A simple process—check power and airflow, observe the start‑up sequence, log symptoms, and make informed calls—can save time, money, and stress. Use the cost ranges here to frame decisions, and lean on licensed professionals when fuel, high voltage, or refrigerant are in play. With a clear maintenance rhythm and a practical troubleshooting mindset, your system can run smoothly through the coldest weeks, keeping comfort steady and expenses predictable.